University of Toledo And U.S. NIH Study Shows That Diets High In Processed Fiber Could Increase Risk Of Liver Cancer

Source; Medical News - Liver Cancer Oct 12, 2022 3 years, 4 months, 1 week, 6 days, 10 hours, 6 minutes ago

A new study by researchers from the University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences, Ohio -USA and the U.S. National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Maryland-USA has found that diets high in processed fiber could increase risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a type of

liver cancer.

The study also involved researchers from Georgia State University, Atlanta-USA and Vall d’Hebron Institut de Recerca, Vall d’Hebron Barcelona Hospital Campus-Spain.

The pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which kills millions annually, is poorly understood. Identification of risk factors and modifiable determinants and mechanistic understanding of how they impact HCC are urgently needed.

The study team sought early prognostic indicators of HCC in C57BL/6 mice, which they found were prone to developing this disease when fed a fermentable fiber–enriched diet. Such markers were used to phenotype and interrogate stages of HCC development. Their human relevance was tested using serum collected prospectively from an HCC/case–control cohort.

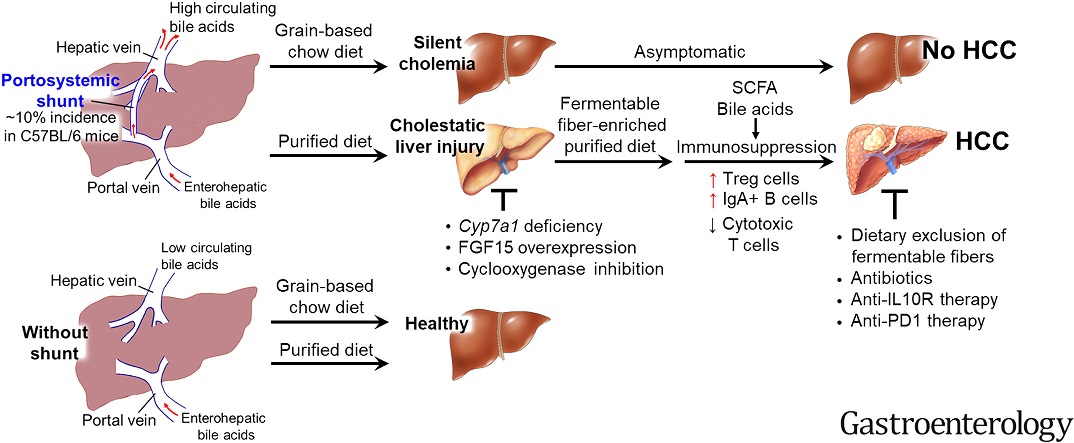

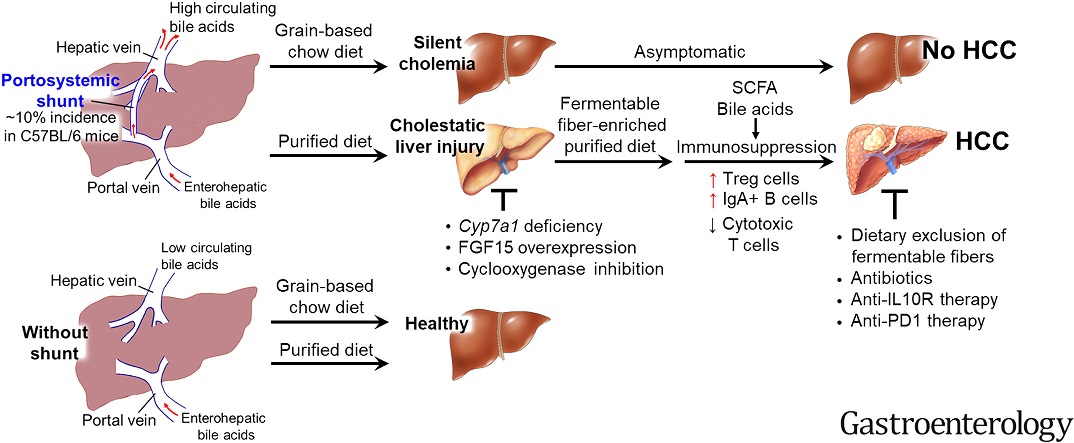

For the study, HCC proneness in mice was dictated by the presence of congenitally present portosystemic shunt (PSS), which resulted in markedly elevated serum bile acids (BAs).

The study findings showed that approximately 10% of mice from various sources exhibited PSS/cholemia, but lacked an overt phenotype when fed standard chow.

However, PSS/cholemic mice fed compositionally defined diets, developed BA- and cyclooxygenase-dependent liver injury, which was exacerbated and uniformly progressed to HCC when diets were enriched with the fermentable fiber inulin.

Such a progression to cholestatic HCC associated with exacerbated cholemia and an immunosuppressive milieu, both of which were required in that HCC was prevented by impeding BA biosynthesis or neutralizing interleukin-10 or programmed death protein. Analysis of human sera revealed that elevated BA was associated with future development of HCC.

The study findings concluded that PSS is relatively common in C57BL/6 mice and causes silent cholemia, which predisposes to liver injury and HCC, particularly when fed a fermentable fiber–enriched diet. Incidence of silent PSS/cholemia in humans awaits investigation. Regardless, measuring serum BA may aid HCC risk assessment, potentially alerting select individuals to consider dietary or BA interventions.

The study findings were published in the peer reviewed journal: Gastroenterology.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(22)00959-3/fulltext

The study team also found that men who had high fiber intake and high blood bile acid levels had a 40% higher risk of

liver cancer.

These days, fiber-enriched foods are often consumed by many individuals to promote weight loss and fend against chronic diseases like cancer and diabetes.

However unknown to many, consuming highly refined fiber, however, may raise the risk of

liver cancer in certain individuals, especially those with a silent vascular deformity, according to the study team.

/>

Senior author, Dr Matam Vijay-Kumar, a professor in the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology in the University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences told Thailand

Medical News, “We have worked for a long time on this idea that all diseases start from the gut. This study is a notable advancement of that concept. It also provides clues that may help identify individuals at a higher risk for

liver cancer and potentially enable us to lower that risk with simple dietary modifications.”

Previously, the study team published another study that revealed a large proportion of mice with immune system defects developed liver cancer after being given an inulin-fortified diet.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30340040/

The compound inulin is a refined, plant-based fermentable fiber that is sold in supermarkets as a health-promoting prebiotic. Additionally, it is often found in processed foods.

The study team found that around one in ten regular, otherwise healthy lab mice got liver cancer after consuming the inulin-containing diet, despite the fact that inulin promotes metabolic health in the majority of those who consume it.

Dr Vijay-Kumar, who is also director of the UToledo Microbiome Consortium further added, “That was very surprising, given how rarely liver cancer is observed in mice. The study findings raised real questions about the potential risks of certain refined fibers, but only now do we understand why the mice were developing such aggressive cancer.”

This new subsequent study offers a clear explanation and may have implications that go beyond laboratory animals.

While the study team furthered its investigation, the team discovered all mice that developed malignant tumors had high concentrations of bile acids in their blood caused by a previously unnoticed congenital defect called a portosystemic shunt.

In normal circumstances, blood leaving the intestines goes into the liver where it is filtered before returning to the rest of the body.

However, when a portosystemic shunt is present, blood from the gut is detoured away from the liver and back into the body’s general blood supply.

Worryingly, this vascular defect also allows the liver to continuously synthesize bile acids. Those bile acids eventually spill over and enter circulation instead of going into the gut.

Furthermore, blood that’s diverted away from the liver contains high levels of microbial products that can stimulate the immune system and cause inflammation.

The study found that in order to keep check on such inflammation, which can be damaging to the liver, the mice react by developing a compensatory anti-inflammatory response that dampens the immune response and reduces their ability to detect and kill cancer cells.

Graphical Abstract

Although all mice with excess bile acids in their blood were predisposed to liver injury, only those fed inulin progressed to hepatocellular carcinoma, a deadly primary liver cancer.

Graphical Abstract

Although all mice with excess bile acids in their blood were predisposed to liver injury, only those fed inulin progressed to hepatocellular carcinoma, a deadly primary liver cancer.

Importantly, 100% of the mice with high bile acids in their blood went on to develop cancer when fed inulin. None of the mice with low bile acids developed cancer when fed the same diet.

First author, Dr Beng San Yeoh, a postdoctoral fellow at University of Toledo added, “Dietary inulin is good in subduing inflammation, but it can be subverted into causing immunosuppression, which is not good for the liver.”

Distinguished University Professor and chair of the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology at University of Toledo, and a co-author of the study, Dr Bina Joe, said the high-impact publication demonstrates the pioneering research being done at University of Toledo.

She commented, “The role of the gut and gut bacteria in health and disease is an exciting and important area of research, and our team is providing new insights on the leading edge of this field.”

The study findings could provide insight that might help clinicians identify individuals who are at higher risk of

liver cancer years in advance of any tumors forming.

At present, portosystemic shunts in humans are relatively rare ie the documented incidence is only one in 30,000 individuals at birth. However, given that they generally cause no noticeable symptoms, the true incidence may be many times greater.

Interestingly, portosystemic shunting also commonly develops following liver cirrhosis.

The study team theorizing that high bile acid levels might serve as a viable marker for

liver cancer risk, tested bile acid levels in serum samples collected between 1985 and 1988 as part of a large-scale cancer prevention study.

It was found that in the 224 men who went on to develop

liver cancer, their baseline blood bile acid levels were twice as high as men who did not develop

liver cancer.

Detailed statistical analysis also found individuals with the highest blood bile acid levels had a more than four-fold increase in the risk of liver cancer.

The study team also sought to examine the relationship between fiber consumption, bile acid levels, and

liver cancer in humans.

Although existing epidemiological studies don’t differentiate between soluble and non-soluble fiber, the study team could look at fiber consumption in concert with blood bile acids.

Typically, there are two basic types of naturally occurring dietary fiber, soluble and insoluble. Soluble fibers are fermented by gut bacteria into short-chain fatty acids. Insoluble fibers pass through the digestive system unchanged.

The study team intriguingly found high total fiber intake reduced the risk of

liver cancer by 29% in those whose serum bile acid levels were in the lowest quartile of their sample.

Alarmingly however, in men whose blood bile acid levels placed them in the top quarter of the sample, high fiber intake conferred a 40% increased risk of liver cancer.

The study findings suggest both the need for regular blood bile acid level testing and a cautious approach to fiber intake in individuals who know they have higher-than-normal levels of bile acids in their blood.

Dr Vijay-Kumar added, “Serum bile acids can be measured by a simple blood test developed over 50 years ago. However, the test is usually only performed in some pregnant women. Based on our findings, we believe this simple blood test should be incorporated into the screening measurements that are routinely performed to monitor health.”

Although the study team are not arguing broadly against the health-promoting benefits of fiber, they are urging attention to what kind of fiber certain individuals eat, underscoring the importance of personalized nutrition.

The study team warned, “All fibers are not made equal, and all fibers are not universally beneficial for everyone. Individuals with liver problems associated with increased bile acids should be cautious about refined, fermentable fiber. If you have a leaky gut liver, you need to be careful of what you eat, because what you eat will be handled in a different way.”

For more on

Liver Cancer, keep on logging to Thailand

Medical News.